Let’s present a scenario that is familiar to just about every adult. You go to the bank, deposit a physical check or stack of cash into the ATM or a cashier’s waiting hands.

And...that’s likely the furthest you think about the matter.

But have you ever stopped to consider where the contents of that specific deposit go?

Many customers envision their digital “account” being replenished with more funds, but does a physical equivalent of your digital “account” actually exist?

No, at least not as you may imagine it to. This is the case, in part, because of a financial system that allows for fractional reserve banking (more on this in a bit).

Despite banks holding far less of their customers’ money than most realize, a substantial portion of the public believes that the precise amount of money in their account is being held in some physical space.

Extrapolate this view to the totality of customers who have a checking and/or savings account at any bank, and you may believe that banks hold all of their customers’ funds in a physical vault, ready for withdrawal at any moment.

You would not be alone in thinking this.

In a recently conducted study of 1,000 US consumers, we asked: does your bank need to hold the exact amount of money that customers deposit at all times?

52% of respondents said no, 26% said yes, and 20% said they do not know.

In case it is still not clear, the 52%ers are correct.

Fractional Banking Means Banks Only Hold a Fraction of Deposits

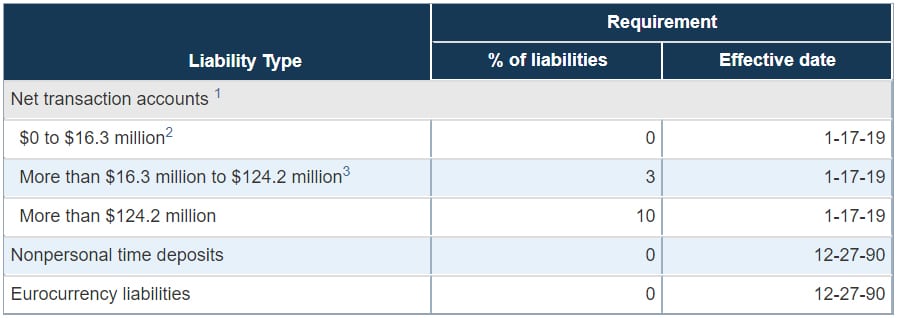

The federal reserve updated its reserve requirement table in January of 2019. They ruled that all banks with more than $124.2 million in deposits must maintain 10% of their deposits in their physical reserves. That 10%, or 1/10th, is the ‘fraction’ of customer deposits that banks must, by law, keep on hand.

Bank Reserve Requirements by Fed. Source: Federal Reserve

Bank Reserve Requirements by Fed. Source: Federal ReserveBanks holding between $16.3 million and $124.2 million in customer deposits, however, must only hold 3% of their deposits in their physical reserves.

With these figures in mind, we found that just 9% of respondents to our study fully understand how much money their bank needs to hold in their reserves at any given time, while most respondents (43%) admitted that they did not know how much a bank must hold.

Ultimately, a better understanding of fractional banking means that Americans will better understand where their money is most likely to be at any given moment.

What is fractional reserve banking?

I already explained the basic idea behind fractional banking: that a federal reserve-compliant bank must maintain only a fraction of its customers’ deposits in immediately-available reserves. The Fed sets the reserve requirement, which is the official term for the percentage of deposits a bank must keep on hand as cash.

So, where does the remaining 90% (or more, in some cases) of those deposits go?

Typically, a bank will put its unheld reserves towards loans, whether to other banks or to customers in the form of mortgages, business loans, and personal loans.

The rationale behind fractional reserve banking is that it allows money to flow more freely throughout the economy, creating a level of stimulus that wouldn’t be possible if banks were required to hold 20% of deposits in reserves, let alone 100% of them.

How do banks make money from your money?

Fractional reserve banking allows banks to lend out money. Each of those loans garners additional revenue for the bank in the form of interest payments from the borrower.

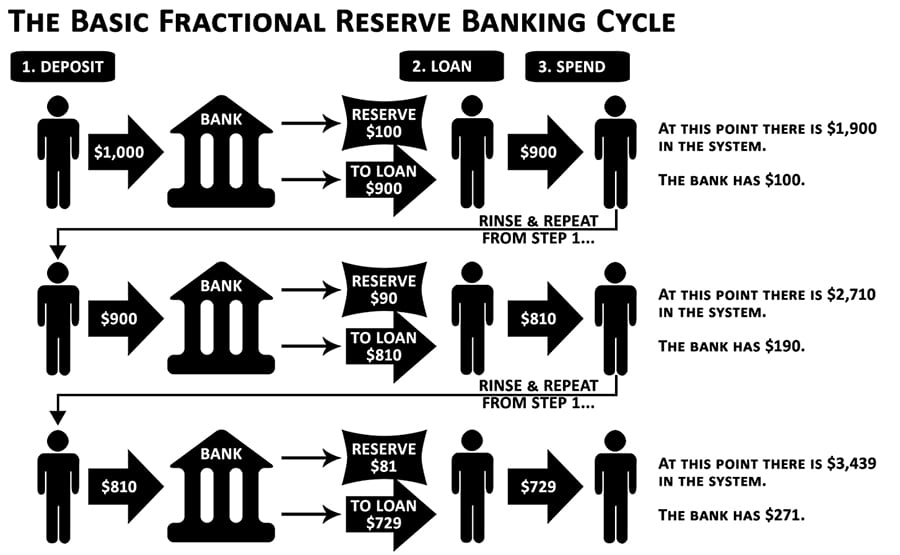

As this cycle of depositing money to banks — and the banks lending that money out to other banks and customers — gains steam, a phenomenon known as the money multiplier effect (or the fractional reserve multiplier effect) takes hold.

Fractional Reserve Lending Cycle. Image via Medium post

Fractional Reserve Lending Cycle. Image via Medium postHere’s a basic breakdown of how the multiplier effect works:

Bank A lends out the 90% of its deposits that it is legally allowed to to Bank B. Bank A’s accounting books still show that it possesses 100% of those deposits, even though they only physically retain 10% of them.

By the same token, Bank B adds the borrowed funds, equivalent to 90% of Bank A’s deposits, to their balance sheet. It does not count the borrowed money as debt, but instead as current assets that it may re-lend out, collecting interest of their own. After all, they can lend that borrowed money out, and they can collect interest on those loans.

In this way, the amount of money in circulation “multiplies” — one could not be blamed for mistaking this effect with magic — with that exponential multiplication creating direct ramifications.

The ramifications cut both ways.

As the money supply grows, consumers should theoretically have greater access to credit, with easier borrowing serving as an economic stimulus. But it’s also the case that the more the money supply grows, the lesser the value of each individual dollar.

In other terms, purchasing power declines. This is why fractional reserve banking and its net effect remains a polarizing topic.

What happens if a bank runs out of money?

In simple terms, the bank and its customers would be sh** out of luck.

If a group of customers accounting for more than 10% of a bank’s deposits were to attempt to withdraw all of their deposits simultaneously, most banks simply wouldn’t be able to grant the request.

That is because the majority of banks take full advantage of the 10% requirement, loaning out the remainder of deposits to maximize their revenue.

And while such a scenario is highly unlikely, it’s not unprecedented. A drastic decline in consumer confidence led to a run on the banks nearly 100 years ago, and as banks were unable to provide their customers with their deposits, one bank after another failed.

The ultimate result of this domino effect: the Great Depression.

In theory, the federal reserve has enough cash on hand to provide funds for its member banks in instances where they do not have enough cash on hand to pay its customers’ withdrawals. More typically, a bank is able to liquidate its accounts receivable and replenish their reserves in order to accomodate any outsize withdrawal.

But, in cases where enough banks of large enough size lend out their money recklessly , the result can be catastrophic (see: subprime mortgages and the 2008 financial crisis).