Smart contracts feel like rules carved in stone, but attackers move like water, always looking for the smallest crack. This guide breaks down the most common ways contracts fail across DeFi, token systems, and apps built on smart contracts, with real world examples and practical defenses.

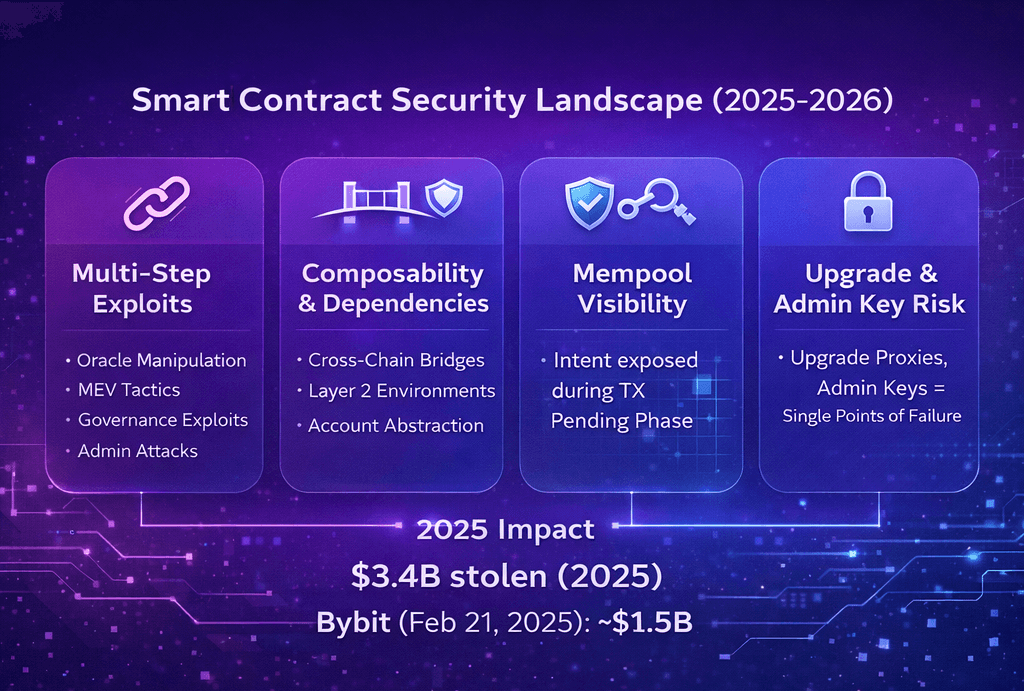

Losses remain huge today, but the mix has shifted toward multi vector exploits that blend bridges, oracles, MEV tactics, governance moves, and admin control abuse. It is written for users, investors, and developers, so you can spot red flags, understand what went wrong, and recognize what safer design looks like.

Note: This is educational security awareness, not financial advice.

Top 5 Smart Contract Attacks

Reentrancy

- Risk: Funds get drained when a contract hands over control before finishing its own bookkeeping.

- Famous incident: The DAO exploit involved about 3.6 million ETH being diverted.

- Prevention: Follow checks effects interactions and use a guard such as ReentrancyGuard.

Flash loan plus oracle manipulation

- Risk: Temporary capital pushes prices into an unsafe state long enough to borrow or withdraw against a false value.

- Famous incident: The PancakeBunny flash loan attack extracted about $45 million.

- Prevention: Use time based pricing such as the Uniswap oracle plus deviation checks and liquidity requirements.

Access control failures

- Risk: A bad permission check or compromised admin path turns the protocol into a set of unlocked vault doors.

- Famous incident: The Parity multisig hack led to over 150,000 ETH stolen.

- Prevention: Use role based controls like AccessControl, protect admin actions with multisig, and add delay with a TimelockController.

Oracle and data feed failures

- Risk: The contract trusts bad, stale, or easily moved data and makes the wrong decision at scale.

- Famous incident: The Mango Markets exploit enabled withdrawals of about $116 million.

- Prevention: Prefer robust feeds like Chainlink Data Feeds and enforce staleness and outlier guardrails.

MEV front running and sandwiching

- Risk: Transaction ordering extracts value from users, often as worse execution and hidden slippage.

- Famous incident: A $25 million Ethereum exploit case centered on transaction ordering mechanics.

- Prevention: Build with MEV in mind and use designs that reduce predictable ordering incentives.

“Red Flags” You Can Spot In 60 Seconds

- Spot price dependency for collateral or liquidations, especially from thin pools.

- Single oracle reliance with no fallback feed or sanity checks.

- Admin can upgrade instantly using proxy style patterns with no delay.

- No timelock and no multisig on treasury or upgrade permissions.

- Weird incentives and tokenomics like infinite mint paths or fragile pegs, a good reminder of why tokenomics matter.

Smart Contract Security Landscape in 2025-2026

In 2025 and 2026, smart contracts remain a major security risk. What’s changed is the shape of many incidents. Instead of one obvious bug, attackers often chain together smaller weaknesses across connected systems to create a much larger failure.

Smart Contracts Attacks Remain a Major Security Risk

Smart Contracts Attacks Remain a Major Security RiskWhat’s Changed since the Early Defi Hack Era

Modern DeFi protocols are built like financial building blocks. That composability is useful, but it means a protocol can inherit risk from its dependencies, including cross chain bridges, Layer 2 environments, and oracles. New wallet patterns also expand the surface area, such as account abstraction via ERC 4337. As a result, many exploits are now multi step, combining bad data, transaction ordering, and privileged actions.

Why Smart Contracts are Still Vulnerable

Immutability can be a strength and a weakness. If code cannot change, a mistake cannot be quietly patched. If it can change through upgradeable proxy patterns, then risk shifts toward who controls upgrades. Smart contracts also operate in public, and transactions can sit in a mempool before confirmation, exposing intent. Finally, high value systems attract professional attackers, and in 2025 over $3.4 billion was stolen, with a February 21, 2025 theft of nearly $1.5 billion in ETH from Bybit showing how a single incident can dominate the year.

Cost of Poor Security

A smart contract audit is usually a predictable cost. A major exploit is not. The fallout can include reputation damage, fast liquidity withdrawals, exchange risk actions, and regulatory scrutiny.

As smart contracts become more interconnected, security becomes less about finding one bug and more about managing the full set of technical and operational risks that surround the code.

Check out our beginner's guide on How To Audit A Smart Contract.

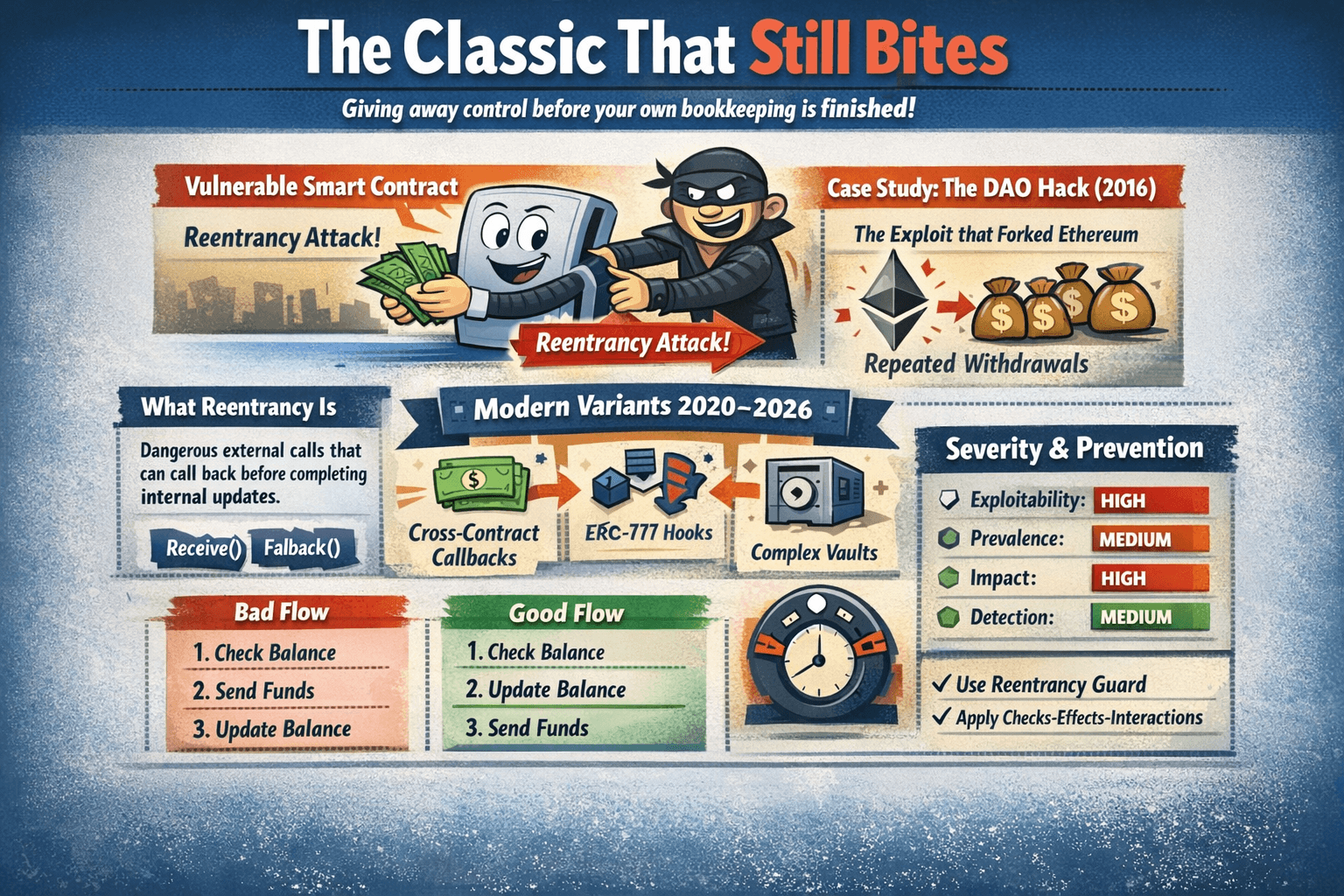

Reentrancy Attacks

A reentrancy attack happens when a contract sends value or calls an external address before it finishes updating its own internal records. It is like a cashier handing you change first, then updating the register after, which gives a thief a chance to interrupt and repeat the same checkout.

It is like a Cashier Handing you Change First, then Updating the Register after

It is like a Cashier Handing you Change First, then Updating the Register afterWhat Reentrancy Is

Reentrancy often shows up around external calls that can execute code, including Solidity fallback and receive functions and other callback patterns. The core issue is control transfer. Once your contract calls out, the other side may call back in before your contract finishes its work.

Case Study: The DAO (2016) And Why it Still Matters

The original The DAO exploit abused a withdrawal flow where funds were sent before the internal balance was reduced. That basic ordering mistake led to repeated withdrawals during the same sequence of calls. The aftermath included the Ethereum hard fork and later regulatory attention such as the SEC report on The DAO. It still matters because the same mistake can return during upgrades, refactors, or new integrations.

Modern Reentrancy Variants

Modern versions often involve cross contract callbacks, token hooks such as ERC 777, and complex vault logic where one external touchpoint can trigger unexpected re entry paths.

Code Lab: Vulnerable Vs Secure Withdraw

Beginner view of the mistake and the fix:

Bad flow:

- Check the user balance

- Send funds to the user

- Update the user balance

Good flow using the checks effects interactions idea:

- Check the user balance

- Update the user balance

- Send funds to the user

A reentrancy guard is like a one at a time lock that prevents the same function from being entered again mid execution. Another approach is pull payments, where users claim funds in a separate step instead of receiving them during a sensitive state change.

Severity Panel + Prevention Quick Guide

- Exploitability: High

- Prevalence: Medium

- Impact: High

- Detection: Medium

Reentrancy is a classic because it targets a timeless mistake: giving away control before your own bookkeeping is finished.

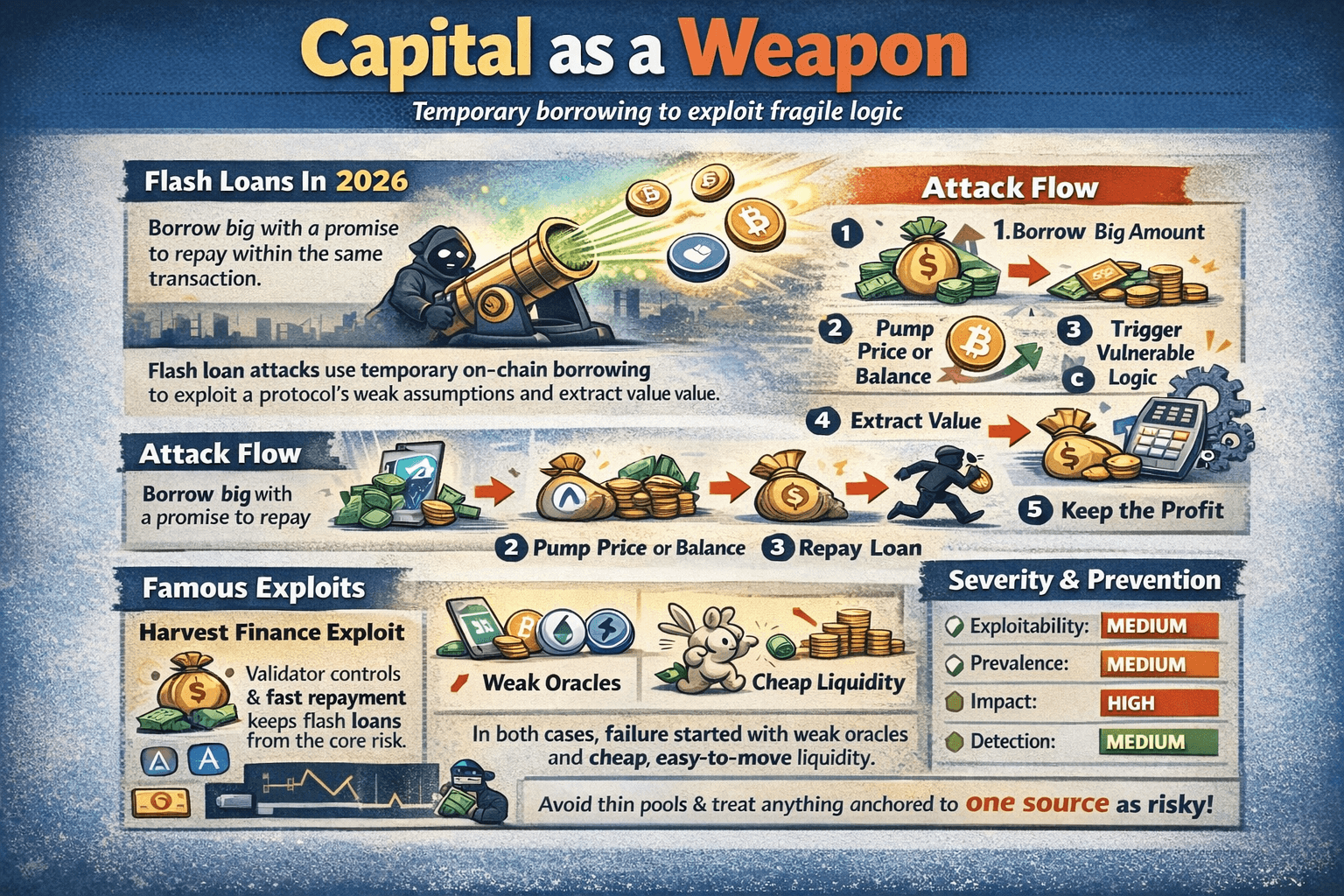

Flash Loan Attacks

Flash loan attacks use temporary on chain borrowing to exploit a protocol that trusts inputs it should not trust. The loan is taken, used, and repaid inside a single transaction, so the attacker can profit without holding capital for long.

Avoid Thin Pools, be Strict with Slippage, and Treat Protocols that Rely on a Single Spot Price as Higher Risk

Avoid Thin Pools, be Strict with Slippage, and Treat Protocols that Rely on a Single Spot Price as Higher RiskTools like Aave flash loans make it possible to borrow large amounts with the requirement that repayment happens before the transaction completes. Flash loans are not the core vulnerability. They magnify weak assumptions around pricing, collateral, and liquidity.

Attack Flow

The common pattern is simple:

- Borrow a large amount,

- Push a price or balance briefly,

- Trigger a calculation that trusts that temporary state,

- Extract value,

- Repay the loan,

- Keep the difference.

Famous Exploits (And The Shared Failure)

In the Harvest Finance incident, an attacker stole about $24 million by abusing pricing and liquidity assumptions. In the PancakeBunny hack, the attacker manipulated exchange rates and extracted value worth about $45 million. Both cases point to the same repeating failure: weak oracle design, fragile pricing assumptions, and liquidity that can be moved cheaply.

Code Lab: Flash-Loan Exploit Pattern

Vulnerable logic:

- Collateral value uses a single spot price from a thin pool

- Borrow limits assume price cannot swing sharply within one transaction

More secure logic:

- Collateral value uses time based or medianized pricing

- Borrow limits reject extreme moves and require meaningful liquidity

Defenses That Work

- Time weighted average price

- Medianization across sources

- Deviation checks and guardrails

- Circuit breakers and pause conditions

- Depth requirements so thin pools cannot set truth

Severity Panel + Prevention Quick Guide

- Exploitability: Medium

- Prevalence: Medium

- Impact: High

- Detection: Medium

What users can do is avoid thin pools, be strict with slippage, and treat protocols that rely on a single spot price as higher risk.

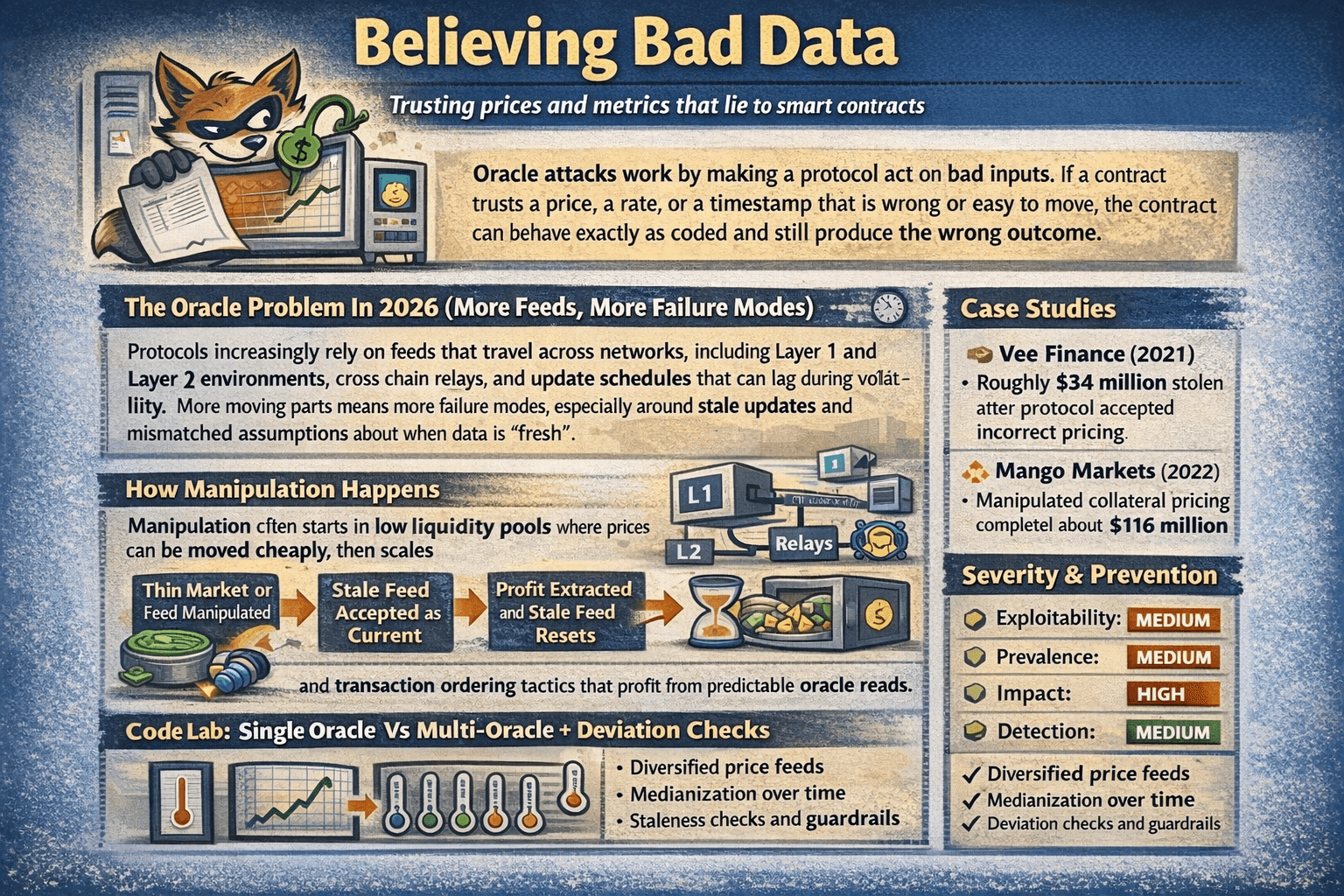

Oracle Manipulation and Data Feed Attacks

Oracle attacks work by making a protocol act on bad inputs. If a contract trusts a price, a rate, or a timestamp that is wrong or easy to move, the contract can behave exactly as coded and still produce the wrong outcome.

Oracle Attacks Work by making a Protocol Act on Bad Inputs

Oracle Attacks Work by making a Protocol Act on Bad InputsThe Oracle Problem (More Feeds, More Failure Modes)

Protocols increasingly rely on feeds that travel across networks, including Layer 1 and Layer 2 environments, cross chain relays, and update schedules that can lag during volatility. More moving parts means more failure modes, especially around stale updates and mismatched assumptions about when data is “fresh.”

How Manipulation Happens

Manipulation often starts in low liquidity pools where prices can be moved cheaply, then scales through flash loan capital. Other paths include stale feeds being accepted as current, and transaction ordering tactics that profit from predictable oracle reads.

Case Studies

The Vee Finance hack shows the core issue in practice, with roughly $34 million stolen after the protocol accepted incorrect pricing. One of the mistakes made by the protocol was using only a single oracle for determining the price of assets used in trading.

A larger example is the Mango Markets exploit, where manipulated collateral pricing enabled the withdrawal of about $116 million.

Earlier cases like the bZx exploit illustrate how even smaller distortions can be profitable when a protocol trusts thin market prices. Attackers phished a bZx developer and stole the mnemonic/private keys that controlled the protocol’s Polygon + BSC deployments, giving them “admin-level” control without needing a code bug.

Code Lab: Single Oracle Vs Multi-Oracle + Deviation Checks

Single source pricing is one thermometer on one wall. Safer designs combine sources, take a median, and refuse outliers with guardrails. Systems like Chainlink Data Feeds expose patterns such as reading from an AggregatorV3Interface and checking update freshness, while time based designs like the Uniswap oracle reduce reliance on a single spot read.

Severity Panel + Prevention Quick Guide

- Exploitability: Medium

- Prevalence: Medium

- Impact: High

- Detection: Medium

Prevention starts with multi source pricing, staleness checks, and deviation limits. What users can do is avoid protocols that rely on a single spot price, be cautious with thin liquidity markets, and treat unusually generous borrow limits or collateral rules as a risk signal.

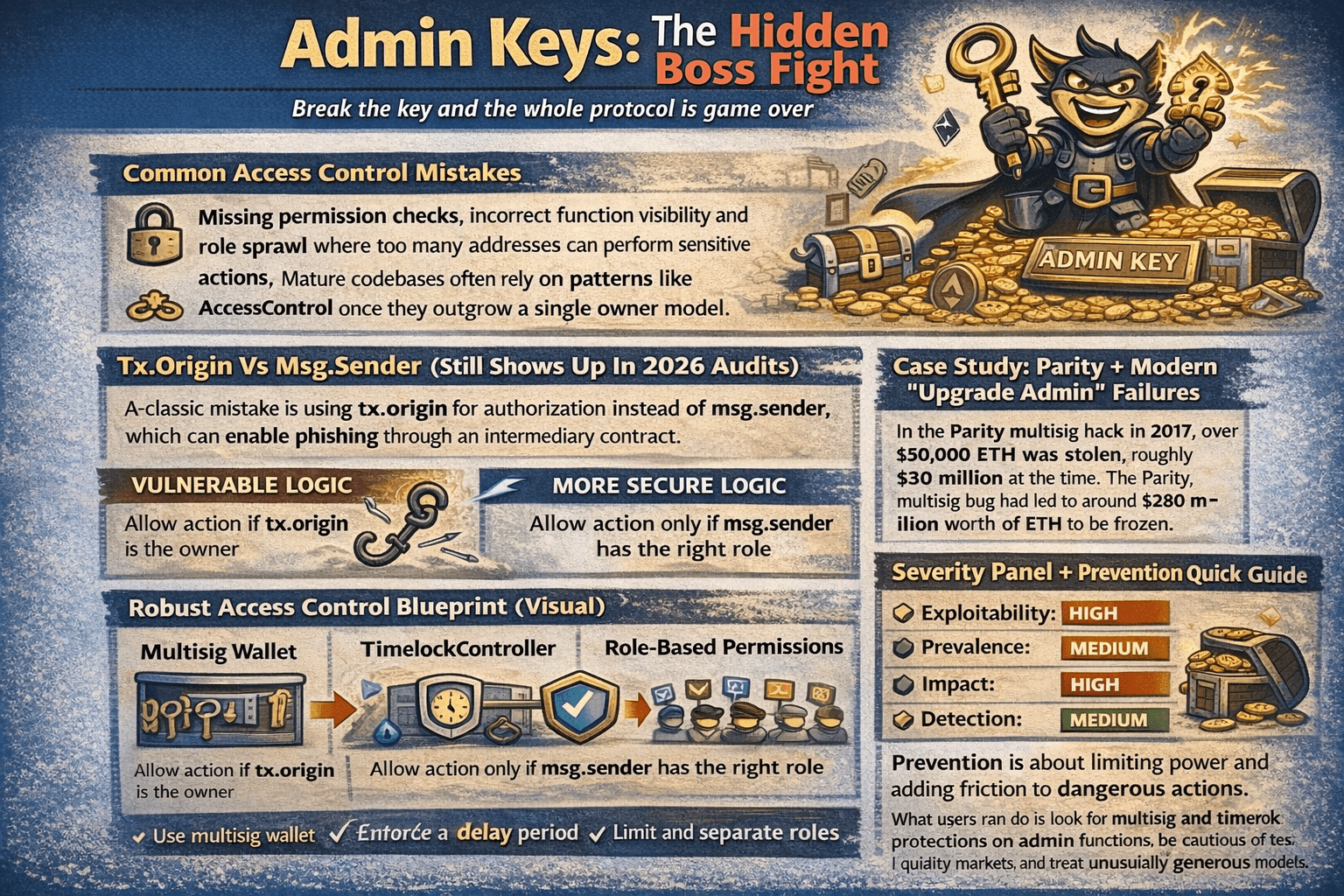

Access Control Failures

Access control decides who can upgrade contracts, pause withdrawals, mint tokens, or move treasury funds. When that permission layer breaks, attackers can simply call a privileged function and bypass everything else.

A Classic Mistake is Using tx.origin for Authorization instead of msg.sender

A Classic Mistake is Using tx.origin for Authorization instead of msg.senderCommon Access Control Mistakes

The most common mistakes are missing permission checks, incorrect function visibility, and role sprawl where too many addresses can perform sensitive actions. Mature codebases often rely on patterns like AccessControl once they outgrow a single owner model.

Tx.Origin Vs Msg.Sender

A classic mistake is using tx.origin for authorization instead of msg.sender, which can enable phishing through an intermediary contract.

Vulnerable logic:

- Allow action if tx.origin is the owner

More secure logic:

- Allow action only if msg.sender has the right role

Case Study: Parity + Modern “Upgrade Admin” Failures

In the Parity multisig hack in 2017, over 150,000 ETH was stolen, roughly $30 million at the time. The Parity multisig bug had led to around $280 million worth of ETH to be frozen. Modern failures often follow the same theme, especially when upgrade authority in proxy patterns can act instantly.

Robust Access Control Blueprint

Strong setups usually combine a multisignature wallet for critical actions, enforced delays with a TimelockController, role based permissions with clear separation, and division of duties so no single key can both propose and execute high impact changes.

Severity Panel + Prevention Quick Guide

- Exploitability: High

- Prevalence: Medium

- Impact: High

- Detection: Medium

Prevention is about limiting power and adding friction to dangerous actions. What users can do is look for multisig and timelock protections on admin functions, be cautious of instant upgrades, and treat unclear permission models as a major risk signal.

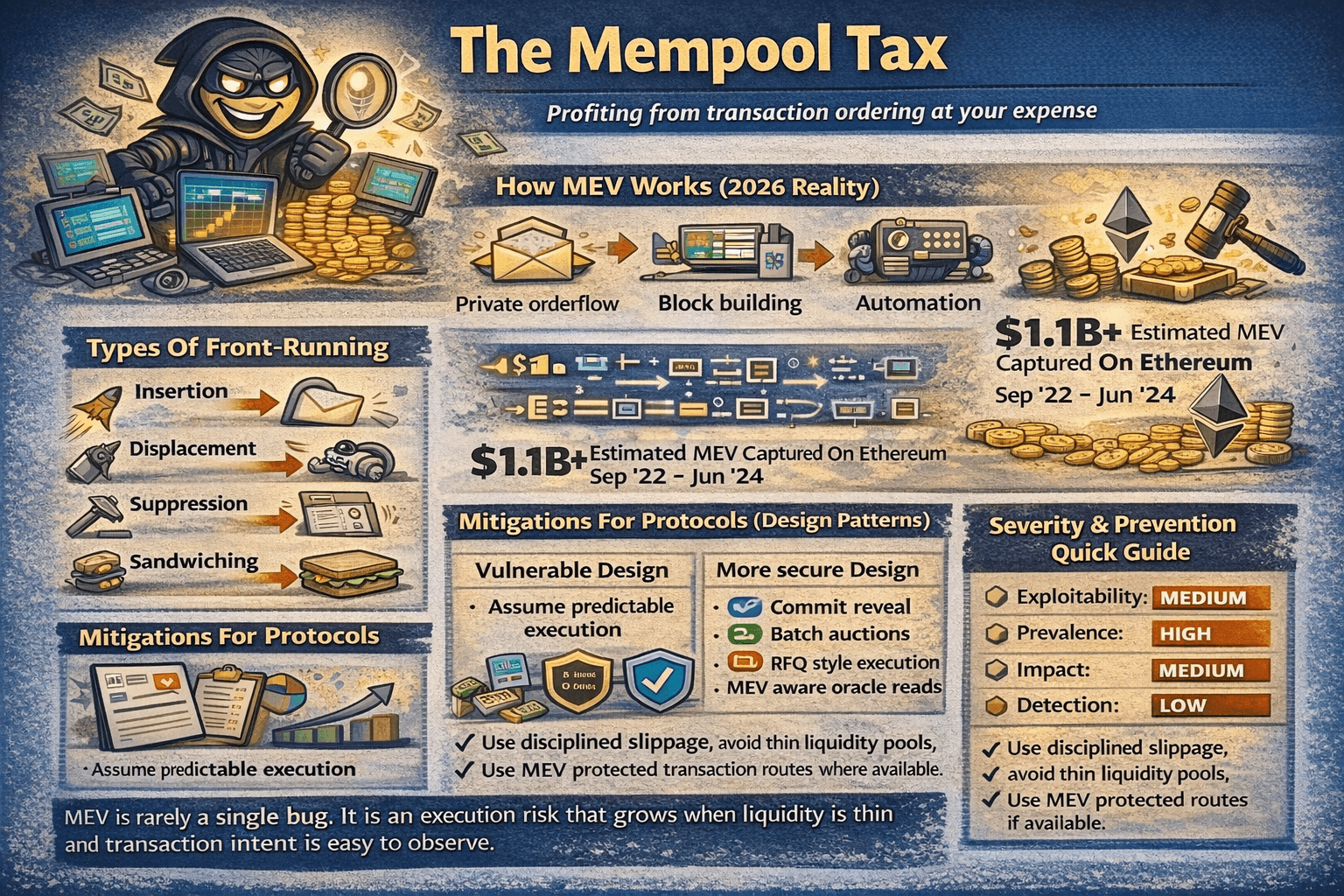

MEV, Front-Running, and Sandwich Attacks

Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) is value captured through transaction ordering. When someone can see pending trades and influence how they land in a block, they can extract profit at the expense of users and protocols.

MEV is Value Captured through Transaction Ordering

MEV is Value Captured through Transaction OrderingHow MEV Works

Most MEV activity happens during block building, where validators and builders select and order transactions. A key enabler is private orderflow and automation that reacts to what it sees in the mempool. On Ethereum, a regulator summary of Flashbots transparency data estimated 526,207 ETH of realized extractable value between September 2022 and early June 2024, roughly $1.1 billion in that period.

Types Of Front-Running

Insertion places a transaction before yours. Displacement pushes yours back. Suppression delays inclusion. Sandwiching wraps your trade with a buy before and a sell after.

Mitigations For Protocols

Vulnerable design:

- Assume predictable execution and trust spot prices

More secure design:

- Use commit reveal

- Batch auctions

- RFQ style execution

- MEV aware oracle reads.

Mitigations For Users

Use disciplined slippage, avoid thin liquidity pools, and use MEV protected transaction routes where available.

Severity Panel + Prevention Quick Guide

- Exploitability: Medium

- Prevalence: High

- Impact: Medium

- Detection: Low

MEV is rarely a single bug. It is an execution risk that grows when liquidity is thin and transaction intent is easy to observe.

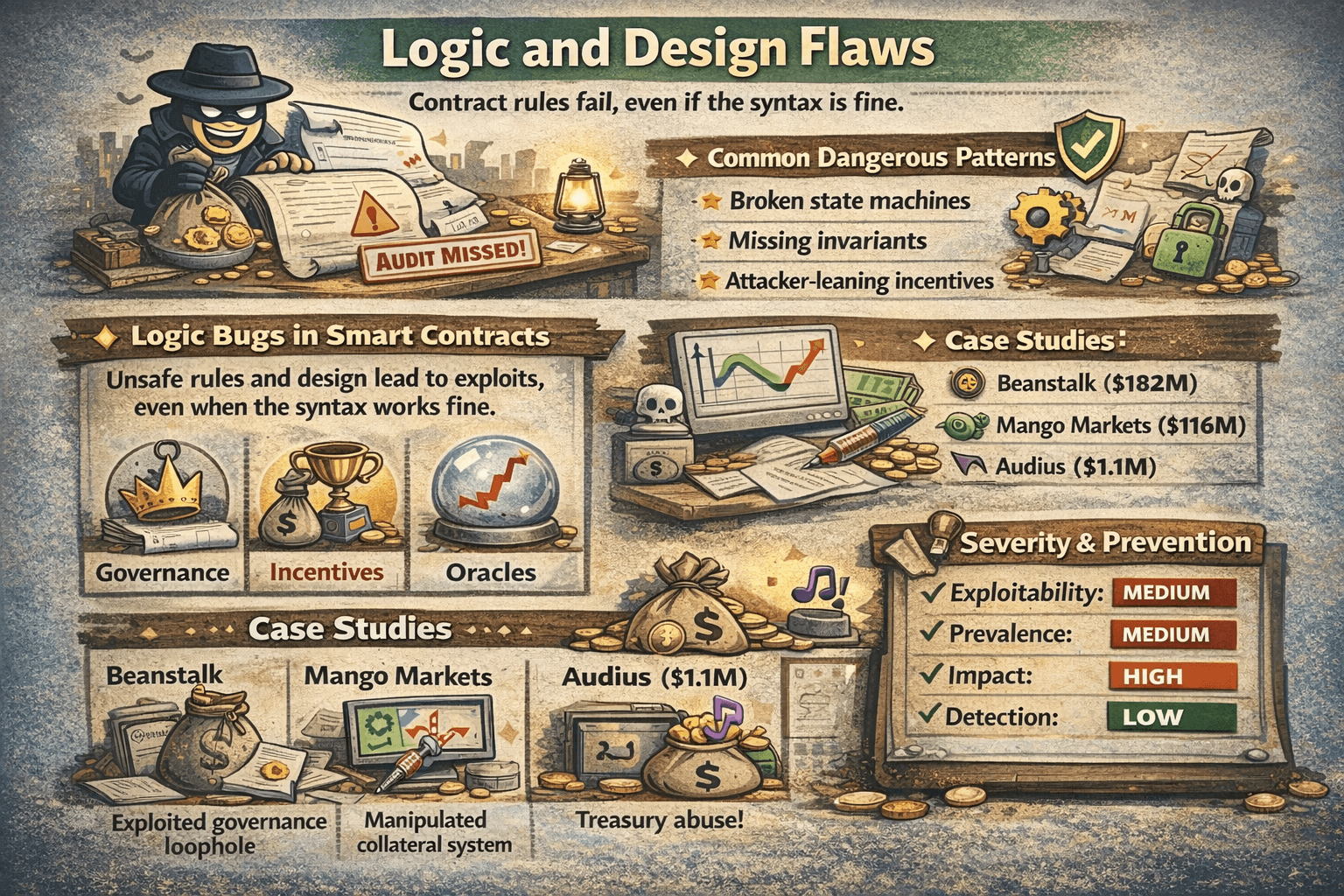

Business Logic and Economic Design Flaws

Business logic flaws happen when the rules are wrong, not the syntax. A contract can run perfectly and still be exploitable if it makes unsafe assumptions about incentives, governance, or how prices should behave. It kind of falls into the “Audit Didn’t Catch This” category.

Logic Bugs are Gaps between what the Protocol is meant to Do and what its Rules actually Allow

Logic Bugs are Gaps between what the Protocol is meant to Do and what its Rules actually AllowWhat Business Logic Bugs Are

These bugs live in the design. They are gaps between what the protocol meant to do and what its rules actually allow.

Common Patterns

Common patterns include:

- Broken state machines,

- Missing invariants,

- Incentive designs that reward attackers more than honest users.

Case Studies

- Beanstalk ($182M): In Beanstalk, the issue wasn’t a single broken line of Solidity so much as a governance design failure. The protocol’s rules allowed an attacker to gain enough control of governance to push through actions that resulted in about $182 million being drained, showing how “working as designed” can still be catastrophic when governance power can be captured.

- Mango Markets ($116M): Mango Markets is a classic example of economic design going wrong via a manipulated collateral system. By distorting the inputs that determined collateral value, the attacker made their position look safer than it really was and was able to withdraw around $116 million, highlighting the danger of relying on valuations that can be pushed out of reality.

- Audius ($1.1M): Audius suffered a smaller but telling failure where a governance exploit in Audius enabled a treasury theft that was ultimately cashed out for about $1.1 million. Even at a lower dollar value, it underscores the same theme: when governance pathways can be abused to move funds, the treasury becomes an obvious target.

Prevention

Vulnerable logic:

- Trust one assumption

Secure logic:

- Test assumptions as adversarial claims and enforces invariants

- Use scenario testing

- Chaos style simulations

- Targeted formal verification when the value at risk justifies it

Severity Panel + Prevention Quick Guide

- Exploitability: Medium

- Prevalence: Medium

- Impact: High

- Detection: Low

What users can do is treat unusually generous rewards, instant governance changes, and systems that rely on a single fragile assumption as higher risk.

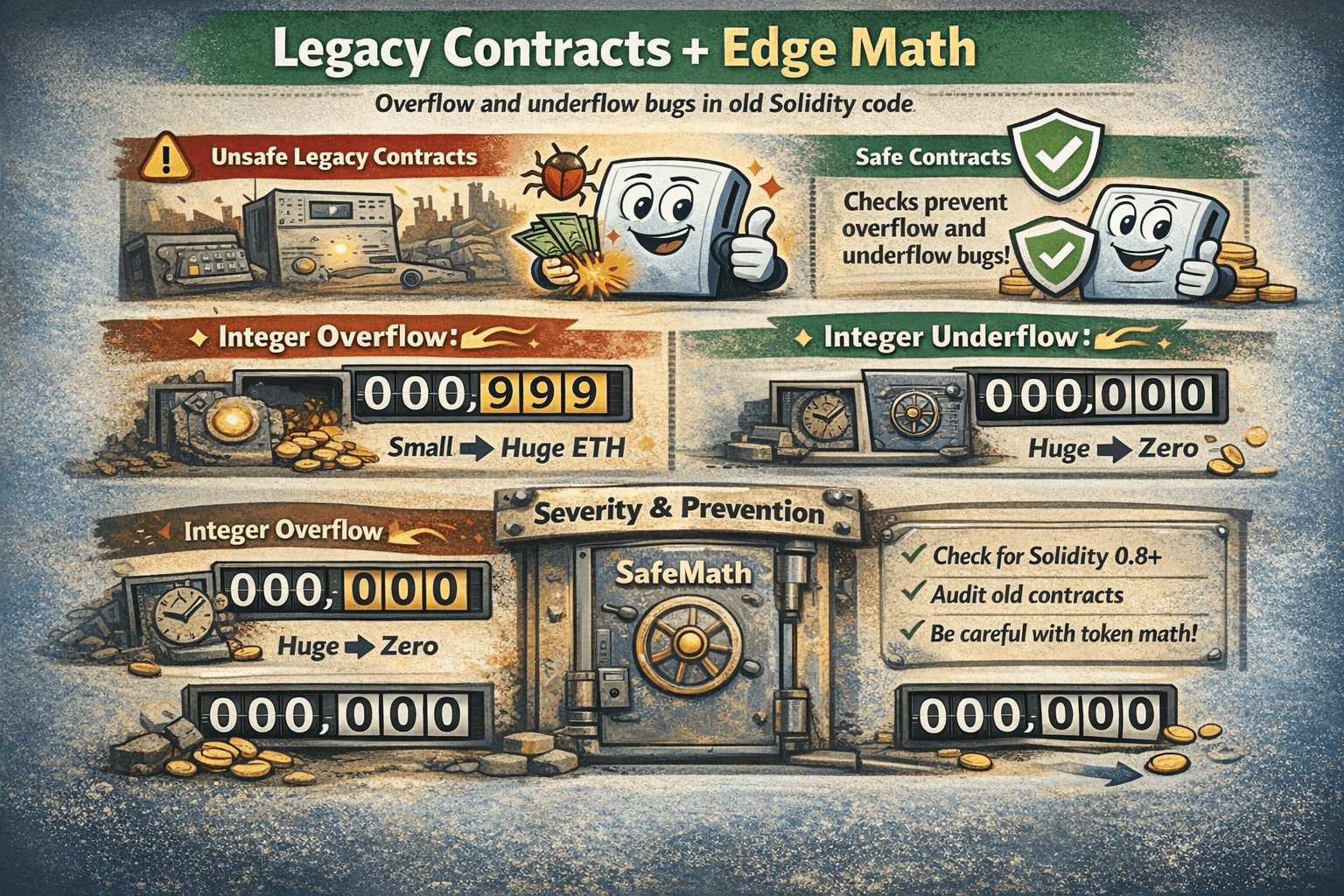

Integer Overflow/Underflow

Integer overflow and underflow bugs happen when math wraps around in a way developers did not intend. This is much rarer in modern Solidity, but it still matters in older deployments and in edge case token math.

Check whether Contracts use Modern Solidity, and Avoid Unaudited Legacy Forks

Check whether Contracts use Modern Solidity, and Avoid Unaudited Legacy ForksWhy It Mattered (Pre-0.8)

Before Solidity 0.8.0, many arithmetic operations could overflow without reverting, meaning a tiny number could suddenly become a huge one.

Code Lab: Vulnerable Vs Safe Math

Vulnerable logic:

- Subtract amount from balance without a guard

- If the balance is smaller than amount, the number can wrap

More secure logic

- Use Solidity 0.8 checked arithmetic

- Add explicit checks that reject impossible states

- Use a proven library pattern like SafeMath when working with legacy codebases

CVE References

The classic batch transfer overflow is tracked as CVE 2018 10299 and the broader class appears in SWC 101. It remains relevant because legacy forks still exist, token math can be unusual, and precision and rounding rules can be gamed. One underflow case, Proof of Weak Hands Coin, lost 866 ETH, roughly $800,000 at the time.

Severity Panel + Prevention Quick Guide

- Exploitability: Low

- Prevalence: Low

- Impact: Medium

- Detection: High

What users can do is check whether contracts use modern Solidity, avoid unaudited legacy forks, and be cautious with tokens that have complex supply or fee math.

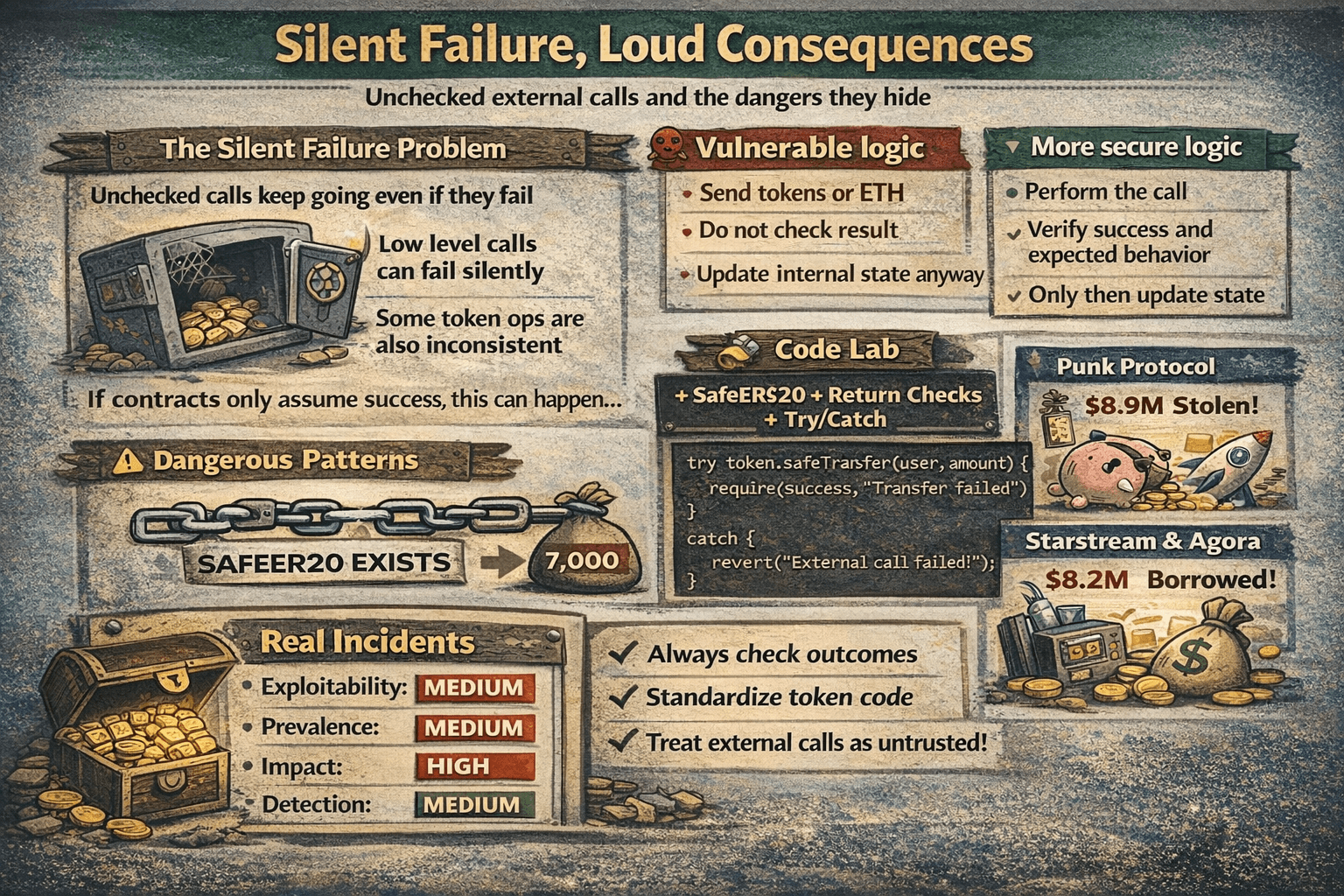

Unchecked External Calls

Unchecked external calls are risky because a contract can keep going even when an external call fails. That can leave balances, accounting, or permissions in a state that looks correct on chain but is logically wrong.

A Practical Fix is to Use SafeERC20 so Failed Transfers do not Quietly Pass

A Practical Fix is to Use SafeERC20 so Failed Transfers do not Quietly PassThe Silent Failure Problem

Low level calls can return a simple success flag rather than halting execution. Some token operations are also inconsistent, which is why wrappers like SafeERC20 exist. If the contract does not confirm what actually happened, it may record success when nothing was transferred.

Dangerous Patterns

Vulnerable logic:

- Send tokens or ETH

- Do not check the result

- Update internal state anyway

More secure logic:

- Perform the call

- Verify success and expected behavior

- Only then update state

Code Lab: Safeerc20 + Return Checks + Try/Catch

A practical fix is to use SafeERC20 so failed transfers do not quietly pass. For external calls that can revert, use try catch to fail safely rather than continuing with partial updates.

Real incidents show how serious this can get, including the Punk Protocol hack with about $8.9 million extracted and the Starstream and Agora hack where about $8.2 million was borrowed after an unsafe external execution path was abused.

Severity Panel + Prevention Quick Guide

- Exploitability: Medium

- Prevalence: Medium

- Impact: High

- Detection: Medium

Prevention is simple: always check outcomes, standardize token interactions, and treat external calls as untrusted. What users can do is prefer protocols that use established libraries like SafeERC20 and avoid systems that rely on fragile integrations where a single failed call could break accounting.

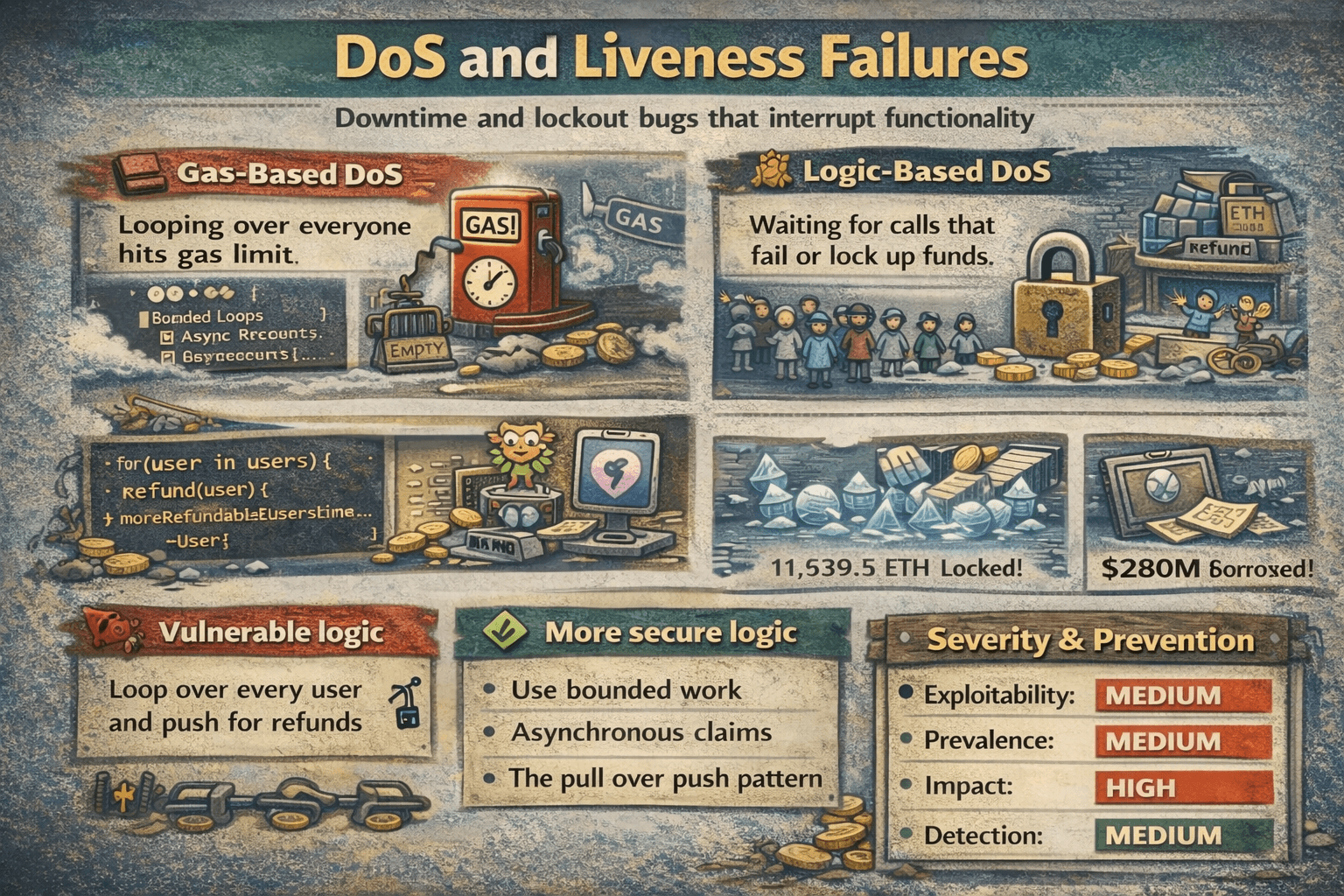

Denial of Service (DoS) and Liveness Failures

A DoS or liveness failure happens when a contract becomes unusable, even if no one directly steals funds. This often comes from designs that can be forced to run out of gas or get stuck waiting for an action that can never succeed.

A DoS or Liveness Failure happens when a Contract becomes Unusable, even if no one Directly Steals Funds

A DoS or Liveness Failure happens when a Contract becomes Unusable, even if no one Directly Steals FundsGas-Based Dos

If a function loops over a growing list, it can eventually exceed the block gas limit and become impossible to execute, a known risk captured in SWC 128 and OWASP SC10.

Logic-Based Dos

Logic based DoS often comes from push style refunds or critical actions that depend on an external call succeeding. A liveness failure can also lock funds, as seen when 11,539.5 ETH was permanently locked in the Akutars incident, and when a bug left roughly $280 million worth of ETH frozen in a Parity wallet event, as mentioned earlier.

Code Lab: Bounded Loops + Async Processing + Pull Payments

Vulnerable logic:

- Loop over every user and push for refunds

More secure logic:

- Use bounded work

- Asynchronous claims

- The pull over push pattern

Severity Panel + Prevention Quick Guide

- Exploitability: Medium

- Prevalence: Medium

- Impact: High

- Detection: Medium

Prevention means designing so no single call must process everyone at once. What users can do is avoid protocols that rely on mass refunds in one transaction and favor systems where withdrawals are user initiated.

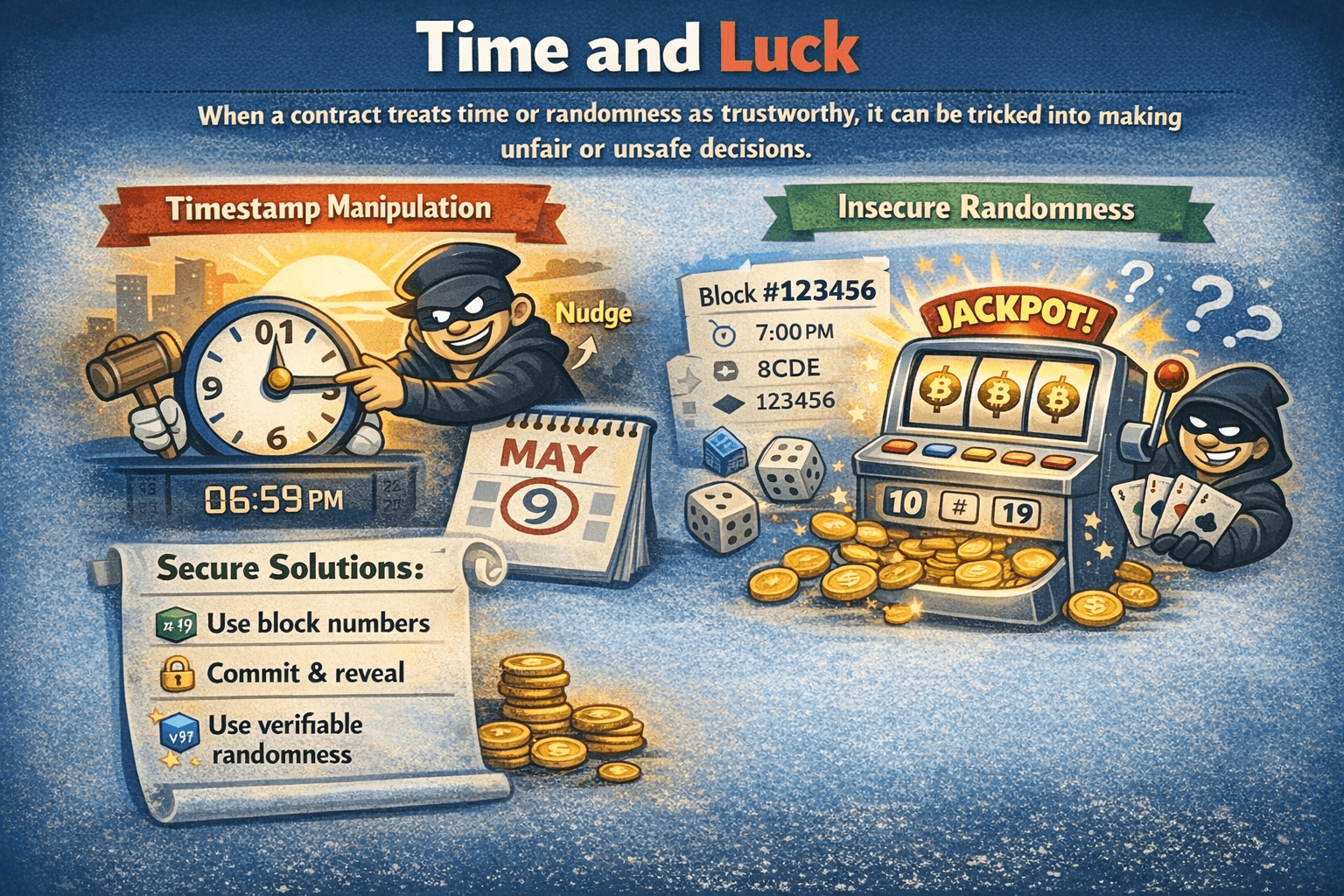

Timestamp Dependence and Randomness

When a contract treats time or randomness as trustworthy, it can be tricked into making unfair or unsafe decisions. On public blockchains, those inputs are often predictable enough that attackers can game them.

Prevention Means never Treating Block Variables as Real Randomness

Prevention Means never Treating Block Variables as Real RandomnessTimestamp Manipulation

If critical logic relies on block.timestamp, validators can sometimes nudge timestamps within acceptable ranges. That is why timestamp dependence is treated as a real attack surface in lotteries, auctions, and vesting.

Insecure Randomness

A common mistake is generating randomness from block data like timestamps, block numbers, or hashes. Because these values are visible and sometimes influenceable, insecure randomness can turn a lottery into a predictable game.

One real example is the Meebits NFT mint exploit (May 2021), where predictable on-chain inputs used for ‘randomness’ enabled an attacker to repeatedly reroll mints until they hit a rare outcome. The attacker ultimately sold the rare Meebit for about 200 ETH (reported at roughly $700k–$765k at the time), showing how weak randomness can translate into meaningful real-world value extraction.

Secure Solutions (Block Numbers, VRF, Commit-Reveal)

Vulnerable logic:

- Use block timestamp as the random seed

More secure logic:

- Use delayed inputs like block numbers for simple timing

- Use commit reveal when participants can wait

- Use verifiable randomness like Chainlink VRF

Severity Panel + Prevention Quick Guide

- Exploitability: Low

- Prevalence: Medium

- Impact: Medium

- Detection: Medium

Prevention means never treating block variables as real randomness. What users can do is be cautious with on chain games that promise luck based wins and favor protocols that use verifiable randomness or transparent commit reveal mechanics.

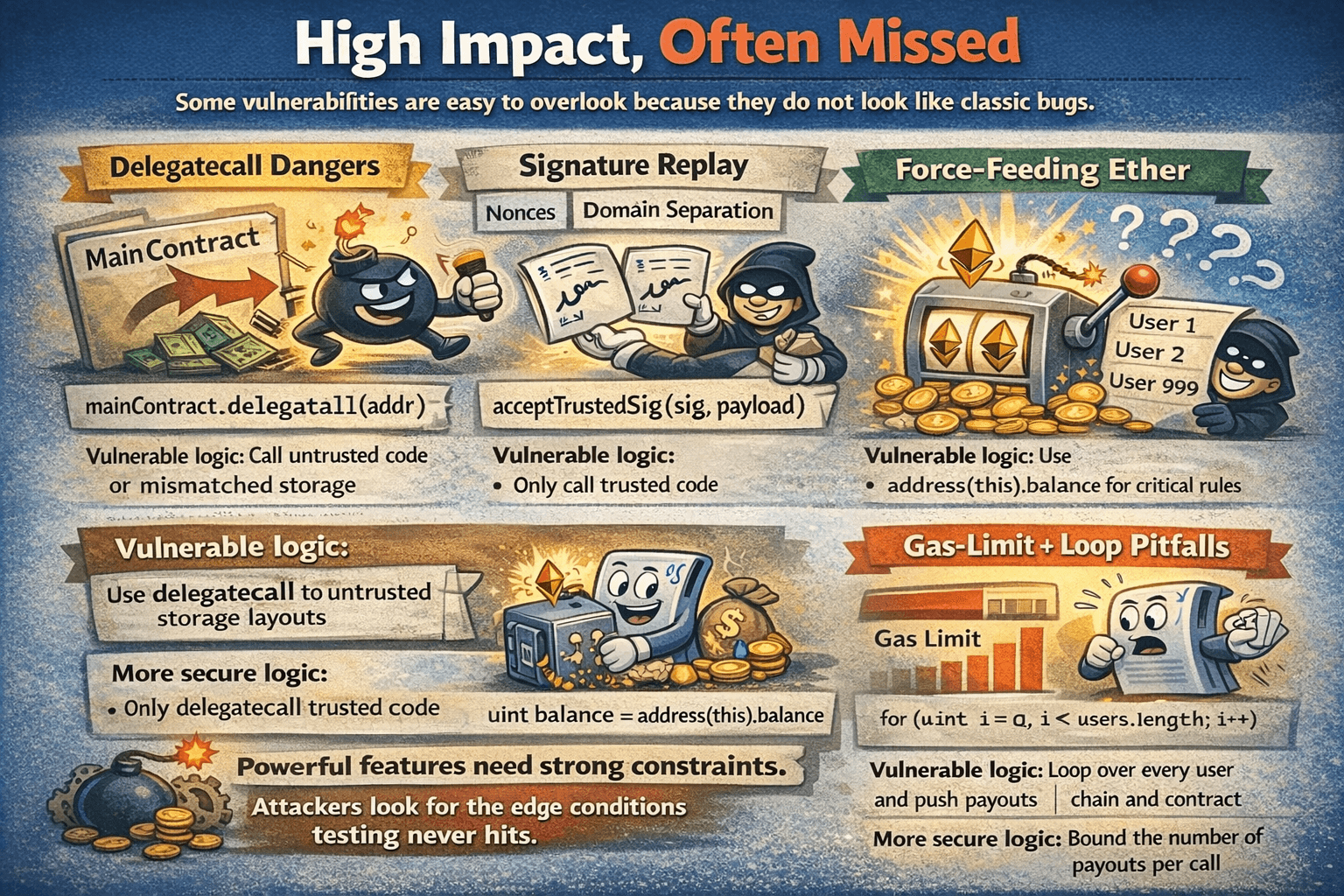

Advanced Vulnerabilities

Some vulnerabilities are easy to overlook because they do not look like classic bugs. They hide in powerful features, signature schemes, and operational assumptions that only break under unusual conditions.

Some Vulnerabilities are Easy to Overlook

Some Vulnerabilities are Easy to OverlookDelegatecall Dangers

Delegatecall lets one contract run another contract’s code while using its own storage. That is useful for libraries and upgrades, but it is risky because the called code can overwrite important state if storage layouts do not match.

Vulnerable logic:

- Use delegatecall to untrusted code or to code with a mismatched storage layout

More secure logic:

- Only delegatecall trusted code and lock storage layouts with careful reviews and tests

A real example of how dangerous contract indirection can be is the Parity multisig wallet hack we discussed earlier, where over 150,000 ETH was stolen, about $30 million at the time.

Signature Replay (Nonces, Domain Separation, Expiries)

Signature replay happens when a valid signature can be used more than once, or used in a different context than the user intended. The fix is to bind signatures to one purpose using nonces, expiry times, and domain separation such as EIP 712.

Vulnerable logic:

- Accept a signature without a nonce check or without chain and contract binding

More secure logic:

- Enforce nonces, include chain and contract details in the signed message, and expire old signatures

This class of issues has shown up in practice, including the 2022 incident where about $15 million of Optimism tokens were stolen after a recovery process was attacked.

Force-Feeding Ether (Selfdestruct Balance Injection)

A contract can receive ETH even if it has no payable function, including through forced transfers. That matters when logic assumes the contract balance only changes through its own functions. This risk is covered in guidance on unexpected Ether transfers.

Vulnerable logic:

- Use address(this).balance as a trusted input for critical rules

More secure logic:

- Track accounting internally and never treat the raw balance as proof of state

Gas-Limit + Loop Pitfalls (Deep Dive)

Some failures happen because a function becomes too expensive to run. If work scales with the size of an array, it can eventually exceed the block gas limit and become unusable, a known issue type in SWC 128 as mentioned earlier.

Vulnerable logic:

- Loop over every user and push payouts

More secure logic:

- Bound the work per call

- Let users claim with pull style withdrawals

- Move heavy work off chain where possible

The common thread across these advanced cases is simple. Powerful features need strong constraints, because attackers look for the edge conditions that normal testing never hits.

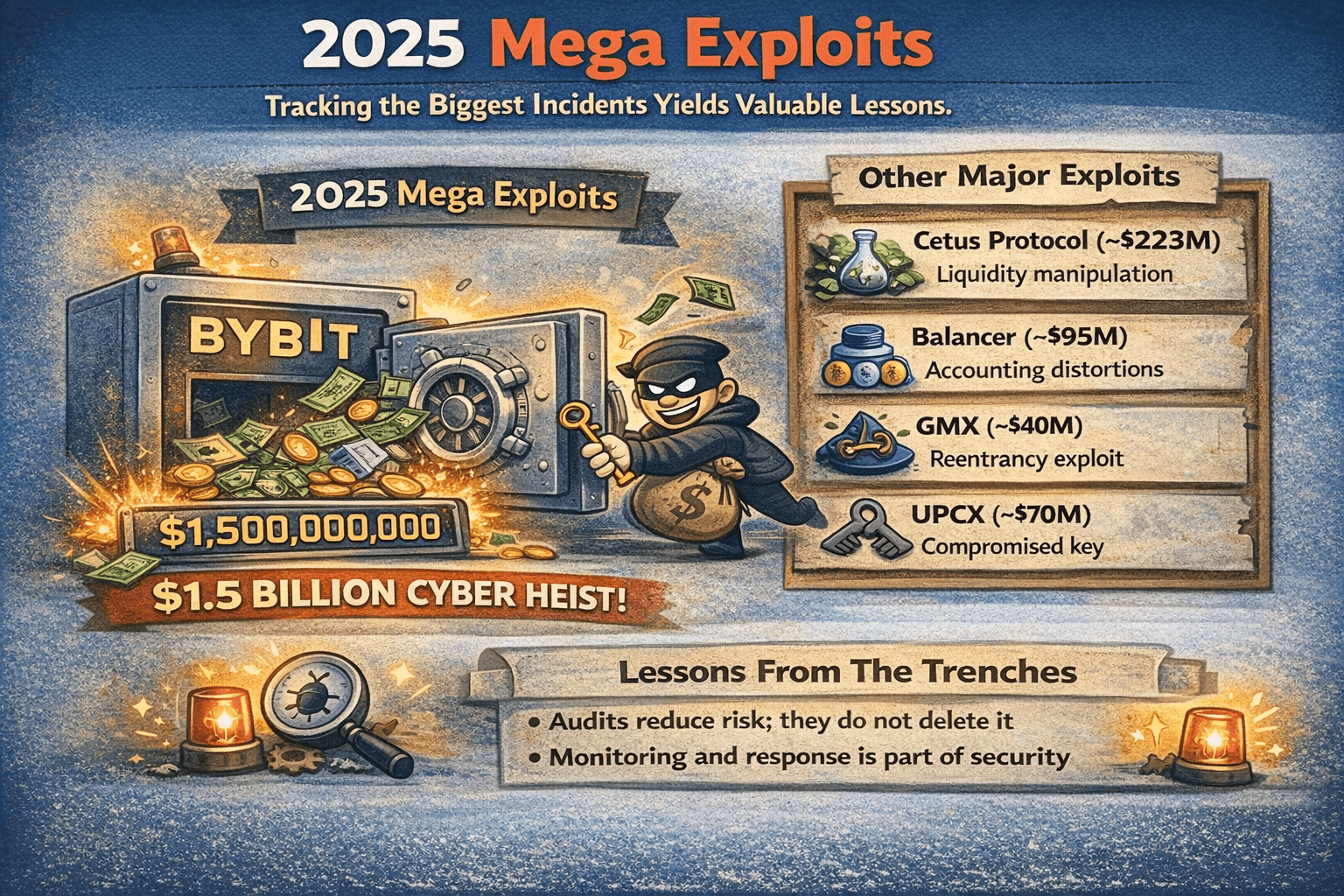

2025 Mega Exploits and How They Actually Happened

A useful way to stay grounded is to track the biggest incidents in the running Crypto Losses reports, then look for the shared mechanics behind them.

A Useful Way to Stay Grounded is to Track the Biggest Incidents and Figure out the "Why" and “How”

A Useful Way to Stay Grounded is to Track the Biggest Incidents and Figure out the "Why" and “How”In 2025, the stand out event was the Bybit theft of approximately $1.5 billion, which shows how devastating key and approval workflows can be when an attacker gains the ability to authorize a transfer.

A few other major 2025 incidents show how “smart contract exploits” can span everything from contract math bugs to admin/key misuse:

- Cetus Protocol (~$223M): Attackers abused a smart contract vulnerability in the DEX’s concentrated-liquidity logic, allowing them to manipulate pool mechanics and rapidly drain liquidity at scale.

- Balancer V2 Composable Stable Pools (~$95M reported by Balancer): A precision/rounding edge case in specific pool types let an attacker distort internal accounting and extract value across multiple pools/chains before mitigations rolled out.

- GMX V1 (~$40M): A re-entrancy-driven exploit in the V1 deployment enabled abnormal state transitions and value extraction; the incident later evolved into a negotiated return/bounty outcome.

- UPCX (~$70M): A compromised privileged key was used to perform a malicious contract upgrade via ProxyAdmin, after which the attacker executed an admin withdrawal function to drain management accounts.

Lessons From The Trenches

- Audits reduce risk; they do not delete it.

- Monitoring and response is part of security.

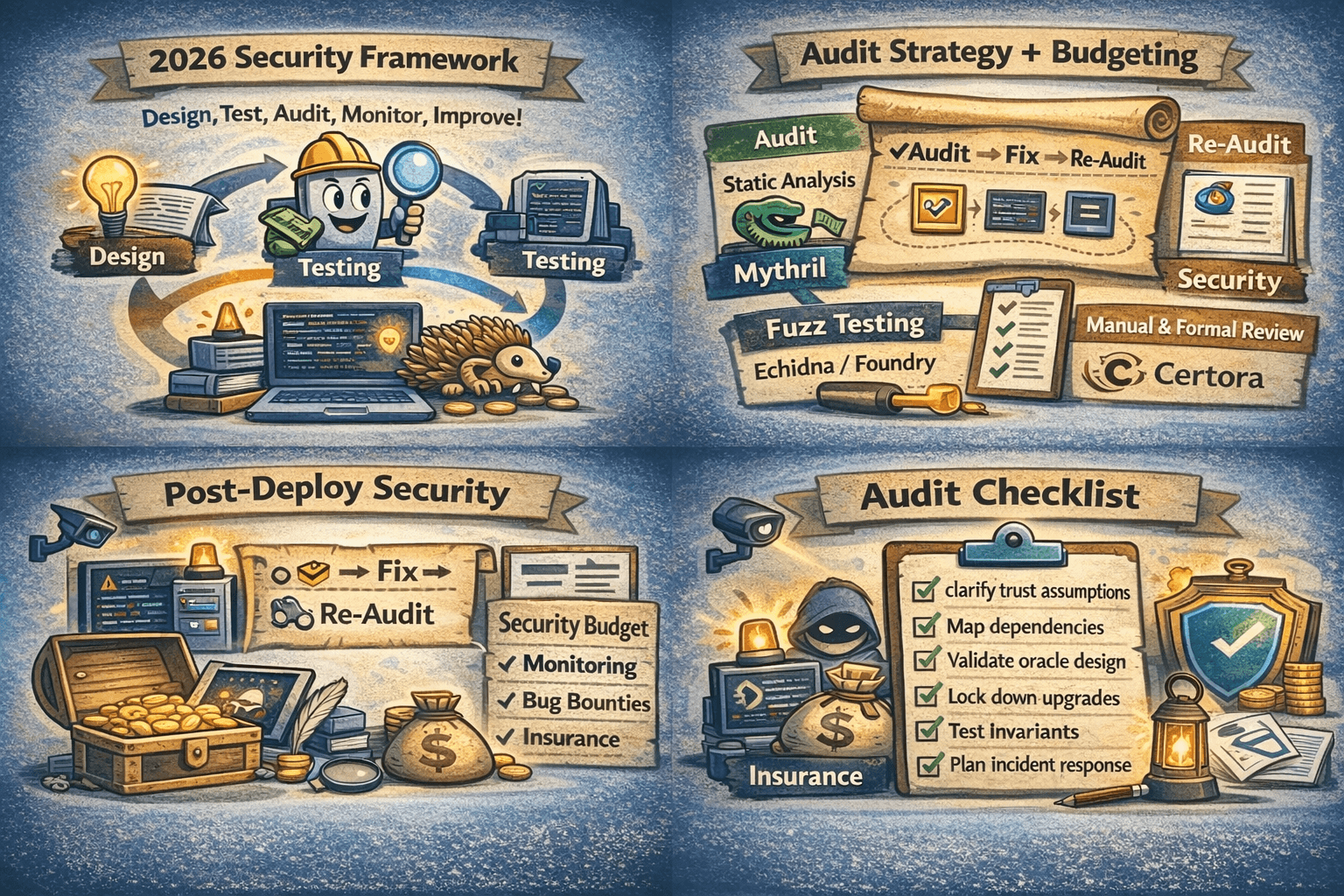

The 2026 Security Framework

In 2026, smart contract security is less about one big event called an audit and more about a workflow that starts before deployment and continues after launch. The goal is to reduce the number of ways a protocol can fail, then shorten the time it takes to detect and contain damage when something still goes wrong.

A Well Rounded Approach Combines Several Types of Testing

A Well Rounded Approach Combines Several Types of TestingTesting Methodology

A well rounded approach combines several types of testing, because each method catches different failure modes.

- Static analysis with tools like Slither to flag common patterns and risky code paths.

- Symbolic execution with Mythril to explore how contracts behave across many possible inputs.

- Fuzzing with Echidna or Foundry to automatically generate adversarial test cases.

- Manual review to validate assumptions that tools cannot understand, such as governance rules and economic incentives.

- Targeted formal verification, for example with Certora, when a small number of properties must be provably true.

Tool Comparison Table

| Tool | Speed | Cost | What it catches | What it misses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slither | Fast | Low | Common bug patterns, risky code constructs | Economic logic, cross protocol assumptions |

| Mythril | Medium | Low to medium | Many execution path issues, constraint based findings | Complex integrations, design intent |

| Echidna | Medium | Low to medium | Invariant breaks, edge cases, unexpected states | What you did not express as a property |

| Foundry | Fast | Low | Practical testing, fuzzing, fork testing | Hard to model long running adversaries |

| Certora | Medium | High | Proving specific properties and invariants | Anything outside the spec you define |

Audit Strategy + Budgeting

A strong audit plan is usually multi round. The first pass identifies issues, then the team fixes them, then auditors verify remediation. Re audit is most important when you change core logic, add a new dependency, expand permissions, or ship a new upgrade path. For readers new to this, a smart contract audit is best treated as one layer in a larger security budget, not the whole budget.

Post-Deploy Security

Post deploy security matters because most losses happen after code meets real users and real liquidity.

- Monitoring for anomalous behavior, including price feed anomalies and unusual admin actions.

- Pause mechanisms that can limit blast radius, such as emergency controls in OpenZeppelin Pausable.

- Responsible disclosure programs and bug bounties, commonly run through platforms like Immunefi.

- Insurance where appropriate, such as coverage options built around mutual models like Nexus Mutual.

Audit Checklist

A simple checklist can keep teams honest:

- Clarify trust assumptions,

- Map dependencies,

- Validate oracle design,

- Lock down upgrades,

- Test invariants,

- Plan incident response before launch.

The practical takeaway is that security becomes real when it is repeatable. If the process is consistent, the protocol is far more likely to survive both honest mistakes and intentional attacks.

Final Thoughts

Smart contracts will never be perfectly safe, but they can be meaningfully safer. The difference usually comes down to boring discipline: careful permissions, resilient price feeds, sensible incentives, and a security process that continues long after launch.

If you remember one thing, make it this. Most “surprise” hacks are only surprising in hindsight because the warning signs were ignored. Learn the patterns, respect the red flags, and treat every protocol like a machine made of many parts, because attackers only need one loose screw.